YLHS Mustang Reagan Fan Recognized in New York Times STEM Writing Contest

Reagan Fan (11) received an honorable mention from the New York Times for her essay regarding bioenergy.

May 10, 2023

Yorba Linda High School (YLHS) is held in high esteem for providing a comprehensive education on a broad range of subjects. However, its self-motivated student body truly rises above and beyond, even outside of school.

Recently, Reagan Fan (11) received an honorable mention from the New York Times for her essay regarding bioenergy. Her essay titled “Crawling Batteries: How Crab Shells Will Replace Your Standard Battery” was entered in the New York Times’ Fourth Annual STEM Writing Contest for the chance to have her work published to The New York Times Learning Network. STEM is an acronym that stands for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math, both as education subjects and career fields.

The Learning Network features educational resources for students and educators primarily from secondary schools. It is completely free, and it provides valuable and accessible learning opportunities.

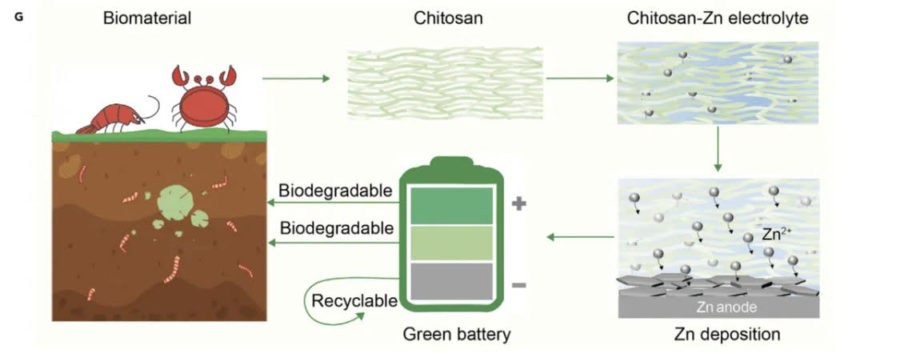

A few months ago, Reagan was reading a National Geographic magazine, where she came across a small excerpt that detailed the topic of her soon-to-be-essay: crab shells as an energy source. Simplified, she discusses how elements in a crab’s exoskeleton (chitosan) can replace current lithium to create a more eco-friendly, sustainable, and safe form of batteries. Reagan’s essay highlights the progress that scientists in STEM are making to create progress in making industries better for our society and Earth.

According to Reagan, “most, if not all, the information I researched was from Liangbing Hu—the director of the University of Maryland’s Center for Materials Innovation (CMI).”

Her eagerness to strive for greatness combined with her timely topic caught the eye of readers at the New York Times. The world of STEM will be seeing more from YLHS’ Reagan Fan.

Read Reagan’s essay below:

How Crab Shells Will Replace Your Standard Batteries

As customers lick their buttery fingers after snapping open the bright red shells of their entrées, they may not know their rigid leftovers are adding to the supply of the secret ingredient that will change the composition of future innovations.

More than ever, batteries are moving towards their peak in demand because of new electric designs meant to lessen fossil fuel consumption. However, the supply response will not keep up for long because of limited resources like Lithium needed to produce batteries. Lithium is the main element in making rechargeable batteries, which are key components in solar panels, power grids, and other electronic mechanisms. Consequently, “global demand for the metal is expected to rise at least 300 percent in the next 10 to 15 years” with lithium becoming scarce in Earth’s crust. On top of that, the process of mining lithium depletes an ecosystem’s water supply and biodiversity. Fortunately, Liangbing Hu, director of the University of Maryland’s Center for Materials Innovation, found a remarkable ingredient that will help substitute the common lithium-ion battery.

Whenever people install batteries, there are always + and – sides to match accordingly; these two divisions are also referred to as the anode and cathode electrodes. Between these electrodes is where ions move with the assistance of a solution called electrolyte to create redox reactions, which generate electricity. Although electrolytes are crucial in actually producing energy, the common lithium salt-based substances used for this are not biodegradable and also flammable, making them susceptible to starting lithium-ion battery fires. The solution, according to Hu, is chitosan: a derivative of chitin found in the exoskeletons of crustaceans, especially in the mighty shells of crabs. Replacing corrosive electrolytes with gel chitosan institutes an eco-friendlier way of obtaining electrolytes and disposing of batteries.

Like killing two birds with one stone, Liangbing Hu and his team also discovered that microbes can decompose two-thirds of the chitosan battery in an approximate period of five months. What is left is zinc: a more plentiful element than lithium, which now can be naturally extracted from the batteries. Moreover, Hu says “well-developed zinc batteries are cheaper and safer”, and from his findings, his batteries are also exceptionally powerful showing 99.7% efficiency after 1000 battery cycles. In other words, after recharging them 1000 times, their performance is still very optimal. With excellent performance and sustainable procedures, the future may not be too far in implementing these batteries in society.

Hu and his team are still behind the lab counter perfecting this potentially revolutionary design, and he hopes “all components in batteries are biodegradable”. Although lithium-ion batteries are still the prominent type of battery for most electric companies like Tesla, the universal goal of carrying out more sustainable practices may lead to the introduction of crab shells in their factories. By merging leftover crab shells with the ubiquitous battery, a leap towards a balance between societal needs and the recovery of our planet is close to achieving.

Featured Sources:

Our 4th Annual STEM Writing Contest – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

To read more about Reagan’s accomplishment, visit this website: Yorba Linda High School student distinguished by New York Times in STEM Writing Contest (pylusd.org)