No Reason to Smile: Vaquita

Vaquitas are an animal species on the brink of extinction.

October 22, 2019

As of now, the world’s most endangered species, the Vaquita porpoise, is on the brink of extinction. Many measures were taken to reverse population trends, but all efforts either failed or were abandoned. According to the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA), current population estimates are around twelve, with a range of six to twenty-two. With such small and dismal numbers, it is unlikely to reverse past mistakes, but it is possible to spread awareness of the Vaquita’s situation.

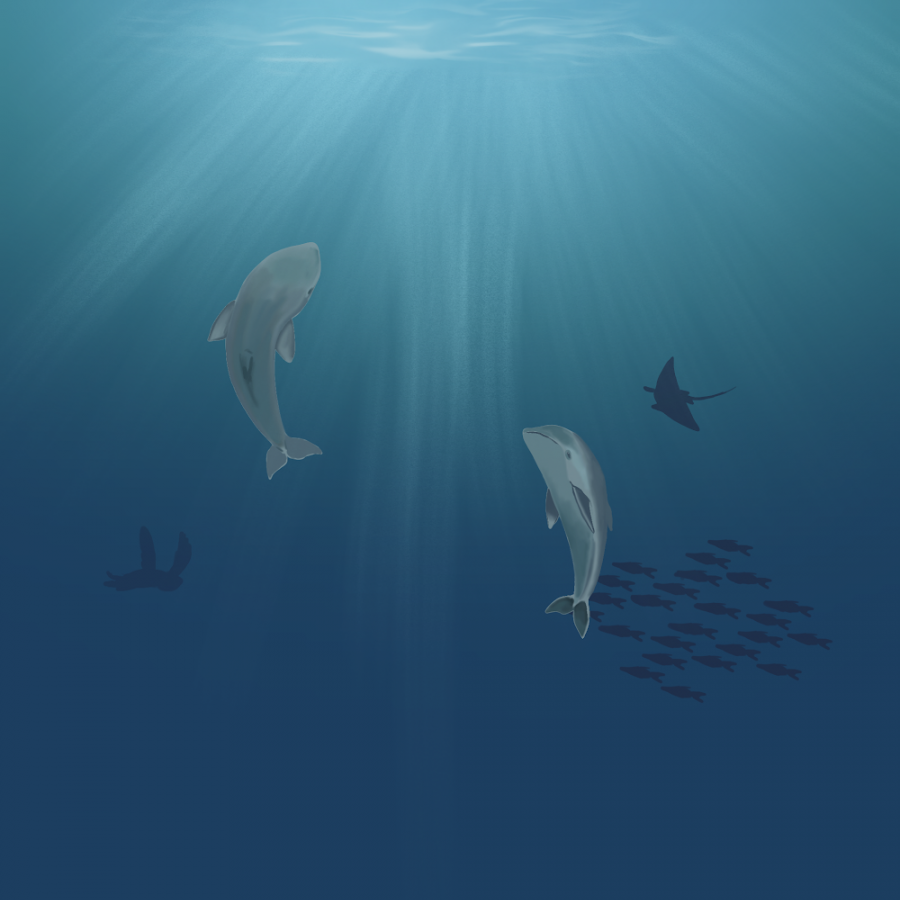

The Vaquitas are porpoises, a species of whale (cetacea) often confused with dolphins. As explained by Ocean Wise, porpoises can be distinguished “…by their smaller size (vaquitas are 4-5 feet), triangular dorsal fins, rounded beaks, and spade-shaped teeth.” It is also worth noting that porpoises tend to be more withdrawn and secluded. The shyness of the Vaquita, combined with its small size, make it nearly impossible to spot them in the wild. In addition, they live only in the northern, coastal waters of the Gulf of California. If found, vaquitas can be identified by their grey coloration, darker areas at their dorsal fin, and lighter areas on their underside. The areas around their mouths are significantly darker, giving the porpoise the appearance of a smile. Unfortunately, the vaquitas have no reason to smile.

Like most endangered species, the vaquita’s reason for endangerment is unsustainable human activity. Humans are not directly hunting for the Vaquita, but they are hunting for the totoaba fish. In China there has been a particular demand for the totoaba swim bladder, the internal organ used to keep the fish afloat. The dried bladder is believed to have medicinal properties, and they can sell for up to $10,000 on the black market. Fisherman have illegally been setting gill nets to catch the totoaba, which unfortunately, shares the same size and location of the Vaquita. Vaquitas often get caught in nets meant for the totoaba, and eventually they drown.

There have been numerous attempts to save the Vaquita, on local and national levels. At the urge of many wildlife organizations, President Enrique Nieto of Mexico banned gill nets in 2015, and enforced the ban with national authorities; the ban was made permanent the following year. The government offered monetary compensation to fishermen who avoided the area of the Vaquita, and went on to establish a Vaquita refuge in the Gulf of California. Researches even attempted to capture and breed vaquitas in captivity, in order to increase their numbers. The project failed when a pregnant Vaquita died before release. With the failure of such national attempts, smaller environmental groups like the Sea Shepherd have started hauling gill nets directly from the gulf. These groups are often met with hostility and violence from local fishermen.

Despite these efforts, recent CIRVA population counts show that the Vaquita population continues to decline. As of now, most sources agree that it is unlikely the Vaquita will survive until 2030, or even 2025. At this point it is not the intent to restore the Vaquita to its 1997 population of 600- that has been deemed impossible even by the International Whaling Commission, who said “current plan[s] to save the Vaquita just won’t work.”

Even here in YLHS, students and staff are not aware of the Vaquita’s situation. When asked about their extinction, Bella Smith (9) said, “What’s a Vaquita?” Now it is more important to remind local communities that they can impact such critical affairs. Students of YLHS need to be conscious of their prevalence as a generation responsible for past mistakes.

A significant part of species conservation is learning from such mistakes, and although some mistakes are irreversible, improvement can begin even here.