Living Under an Illusion

The Flaws of Affirmative Action

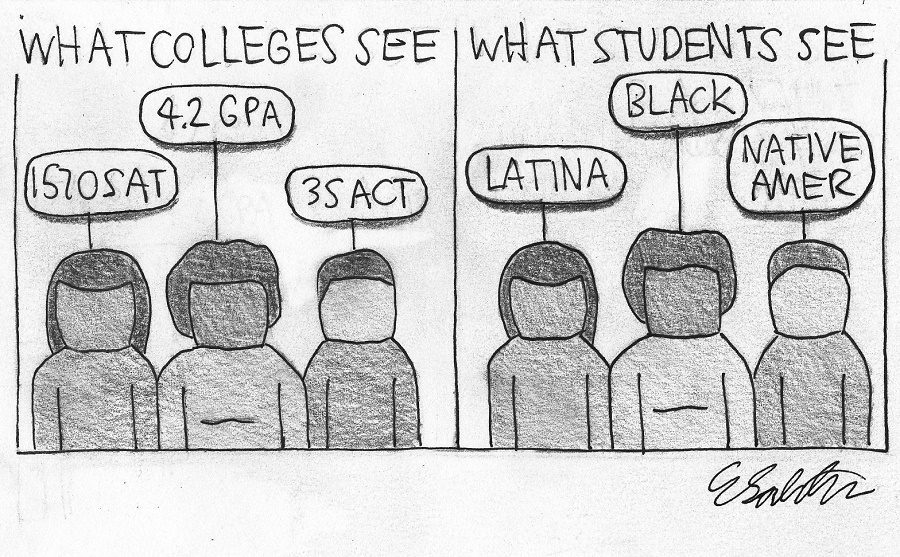

Eli Saletan, The Black and White

Affirmative action is doing more harm than good.

December 15, 2018

Affirmative action is something that has been continued for generations, throughout countries and industries. Yet few people seem to properly consider it or its implications. Recently, however, it has come under fire because Harvard faced a lawsuit for discriminating against Asian applicants through its process of affirmative action. But the scope of the issue extends far past college admissions and is, in fact, something that affects everyone.

Simply put, affirmative action involves policies that favor groups who are or have been historically disadvantaged. These groups can be divided based on race, religion, gender, etc. However, the original meaning was actually the opposite: President Lyndon Johnson used it as a way to have executive officers “hire without regard to race, religion and national origin” (The Economist).

Today, the United States primarily offers affirmative action for African Americans due to the lasting effects of slavery and segregation throughout American history. Similarly, Malaysia offers such advantages to the historically poorer native Malays, India to their dalits or “untouchables.” All of these policies are clearly an attempt to try and make up for injustices or problems in the past.

The issue is, although the concept of affirmative action may seem simple and justified at first, in reality, it is far more complicated. Whereas it is true that the groups being advantaged have been historically disadvantaged, this form of “reverse discrimination” is not the best nor the only solution.

For example, a study by Richard Sander and Stuart Taylor discovered that making it easier for African American students to be accepted into law schools has actually hurt them in the long run; they are more likely to drop out because they lack the skills and preparation that normal policies would have required them to develop. In fact, they also found that there would be more African Americans who could successfully become lawyers if the policies were not based on affirmative action, but rather on “colour-blind policies.”

A similar effect causes African American students as a whole to be at the bottom of their classes, more likely to drop out of university. This is because the affirmative action policies create the “mismatch effect.” Essentially, students are being admitted to schools that they are not adequately prepared for and struggling in difficult classes and universities whereas they could have flourished in a less difficult university or college. Unfortunately, this can often only strengthen the negative view of African Americans; both they and others may perceive them as being less capable than they actually are. Rather, if those students were able to go to schools that properly suited them, they could rise to the top and contribute to overcoming the stereotypes pervasive throughout society (The Atlantic).

Furthermore, there is little evidence as to how successful these affirmative action policies have been. The data shows that it may really be doing more harm than good: “ethnic Malays are three times richer in Singapore, where they do not get preferences, than in next-door Malaysia, where they do.”

Another negative aspect of affirmative action policies is just how divisive they are. The recent Harvard lawsuit is just one example; favoring a certain group of people in society for being disadvantaged will only further the stigmatization against them as other groups may feel like the policies are unfair. In certain cases, they actually are: one American program gives advantages to businesses by “socially and economically disadvantaged” people and these people can still be considered “disadvantaged” if “their skin is the right color,” even if they are “many times richer than the average American family” (The Economist).

Former President Barack Obama further explained the flaws of affirmative action, saying that it would not be fair for his daughters to receive “more favorable treatment than a poor white kid who has struggled more” (The New York Times). His viewpoint showcases the concerns of many in terms of affirmative action policies; these policies are all too often disregarding the fact that even disadvantaged groups have richer and poorer families.

Recently, a stimulation regarding the admission policies of Harvard revealed just how ineffective affirmative action policies are, especially when implemented together with unfair favoritism, such as that for the children of alumni. The stimulation utilized the data of actual Harvard applicants, creating a scenario that eliminated “preferences that tend to help wealthy and white students” and “replace[d] racial preferences with a boost for socioeconomically disadvantaged students of all races.” With these different standards, “the share of underrepresented minority students increased from 28% to 30%,” while the “proportion of first generation college students increased from 7% to 25%.” Above all, the academic performance was still outstanding, “with students averaging at the 98th percentile in SAT scores, and posting excellent high school grade point averages” (The Remedy: Class, Race and Affirmative Action).

Amelie Tran (11) considers affirmative action to be “highly flawed,” and suggests that “everyone starts paying attention to what it is so that we can have better policies.” She shares the sentiments of many, and the Harvard lawsuit is just one step towards doing away with affirmative action in favor of more effective policies.

This is a not a call to stop helping those in society who are or have been disadvantaged by history. However, this is a call to stop using affirmative action as an excuse, an ineffective way of saying that action has been taken. Because affirmative action is simply not enough, and better policies must be created in order to ensure the true equality of society.