The Fear of Infection is More Dangerous than the Infection Itself

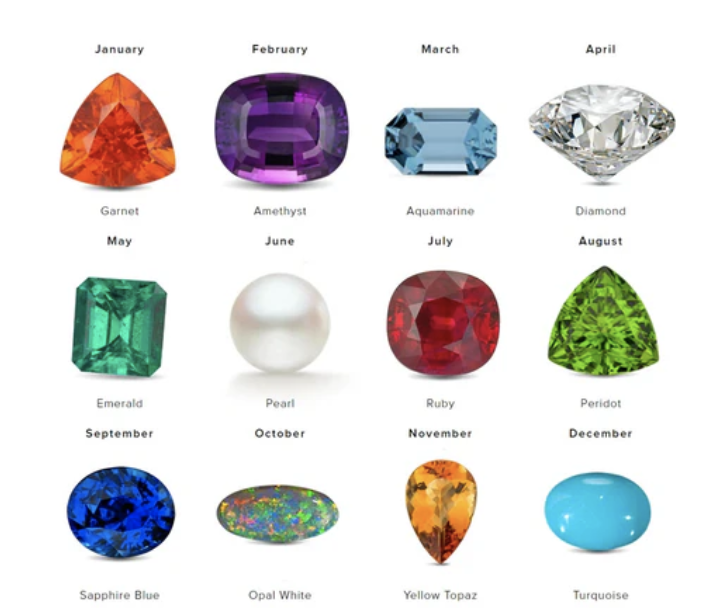

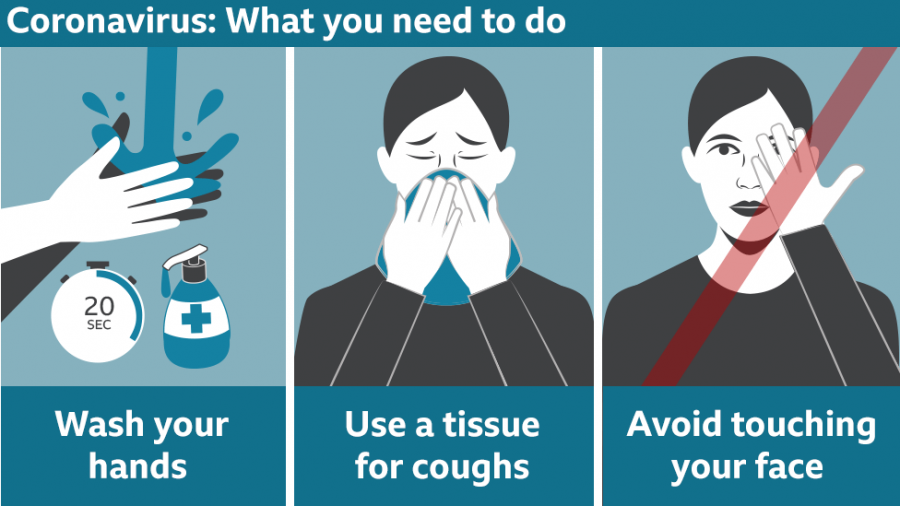

BBC released an image to illustrate the best ways of protecting oneself from the Coronavirus. Nowhere does it stipulate to avoid contact with specific ethnic groups.

March 4, 2020

Earlier this week, I was invited to interview for a scholarship at a university in northern California. As I was boarding my flight to Sacramento, I noticed a young man sitting two rows in front of my assigned seat. As I walked by him, I noticed him begin to cover his mouth, shoving his nose into the collar of his shirt in a blunt and obvious fashion. While I found his behavior quite peculiar, I did not think much of his exaggerated maneuvers. Yet as I sat waiting for our plane to take off, I began to identify a pattern in his behavior. Every time an Asian person walked by, he proceeded to frantically yank at the front of his shirt to cover his nose while shrinking his body into his seat, ensuring that he did not make any physical contact with an Asian passenger.

I would likely be unfazed by this incident on the plane if this type of behavior had not plagued my life since the emergence of the Coronavirus in the past few months. On multiple occasions, I have dealt with strangers cautiously moving around me or peers making comments about the state of my health. Provided that the outbreak was known to have begun in Wuhan, China, those around me see my features and automatically assume that I am somehow a carrier of the infection.

This type of overly-cautious behavior around individuals of Asian heritage is undeniably irritating and unwarranted. But what I find most upsetting about this situation is is the way in which the Coronavirus is being used as ammunition for xenophobic movements and racist ideals. I have heard remarks about “my people” bringing a deadly disease to our nation, that it is reason enough “to send us back to where we came from.”

I am a third generation Asian American. I was born in Baldwin Park, California and have never stepped foot outside of the United States. I am as much of a risk of being a carrier as any other person on that plane. With that being said, I find it entirely offensive that Asian Americans, myself included, are being mistreated because of the outbreak of the infection.

While I may be insulted by this bigoted behavior, I see a negative impact from these ideals that extends far beyond my ego. In all sincerity, I would be lying if I said that I didn’t understand why people are afraid, why they may question my level of contagiousness. I don’t agree with the man’s behavior on the plane, but I can also identify that his actions could be a reflection on his fear of infection. I concede that the fear is genuine, but I must emphasize that worry of contracting Coronavirus is not justification for xenophobia.

The LA Times reports that a Filipino family was “refused a sample at Costco because an employee was concerned about getting infected,” a fact that made me evaluate the unbelievable divide that the infection has prompted.

I know that people are afraid, the prevalence of Coronavirus increasing daily. Students are worried about contracting the virus and have no clue who could be a potential carrier. I fully support taking precautions to avoid infection, but as Jacob Viveros (12) articulated, “being careful consists more so of washing your hands than avoiding your classmates.” We have every right to be afraid, to be cautious as we try to navigate our daily routines in the wake of this terrifying illness. But I will not defend “engaging in prejudicial behavior [to] offer us the comforting fiction that we are helping to fight the disease’s spread” (LA Times).

As a society, we have come so far in terms of reducing the stigmatization of minorities and ending prejudicial attitudes. Thus I refuse to sit back and watch our panic create an environment of racism and dogmatism. We have worked so hard towards acceptance, so, as the LA Times explains, we must terminate the continuation of misinformation and “performative panic” in order to ensure that our fear of contacting the disease does not become “more dangerous than the disease itself.”