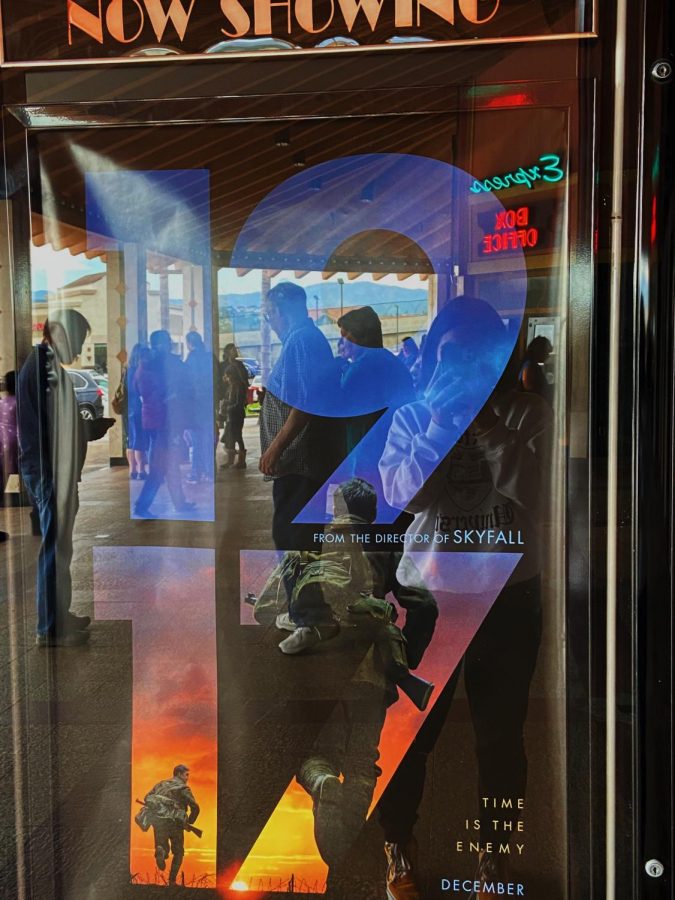

1917: ‘Best Film of 2020’ Review

The movie poster for 1917, a historic film that centers around a mission to stop the British army from falling into a German trap.

January 27, 2020

*WARNING* This article contains information integral to the plot and may contain spoilers.

For the entire movie industry that lusts purely on commissioning the works of overhyped World War II movies: Watch out.

As a person who has been extremely disappointed in the lack of representation that World War I has received in the movie industry, the film 1917 most certainly makes up for the lack of them.

Conveyed as though the entire movie was only filmed in one continuous shot, the camera follows two men from the British army as they are sent on a task to deliver a message to another British post to warn them of a German trap that they would unintentionally walk into if the army decided to attack the retreating Germans the following day.

Lance Corporals Tom Blake and William Schofield are timid, yet determined soldiers who fight for their lives as they involuntarily cover miles of No-Man’s Land, purely on foot.

The presentation of film as though there were no cut scenes or breaks between cuts personalizes the movie as though the audience member watching should feel like they were alongside the two soldiers.

In my opinion, one of the biggest problems between war movies and their audience is the disconnect in which the movie sets between the two. There’s no way to personally apply oneself to the events depicted on the screen, and therefore does not create any sense of “realness” to what’s happening. This is where 1917 is different.

After the level of violence and destruction that World War I imposed on not only its victims but surrounding members of society, many people virtually saw no purpose to life or material items after they witnessed what the horrors of what the reality of war could bring.

This realist way of thinking at the time is ingrained in the thought process of Lance Corporal Schofield, who is revealed to have thrown away an important medal he was awarded for a mere bottle of wine.

Tom Blake, the optimist of the two, took the opportunity of their perilous journey to engage in the telling of funny stories of fellow soldiers. He simply brought Schofield along for the company and back-up, but is confidently determined that they will reach their destination, despite warnings from the general that they will “not even make it ten yards.” Blake later bleeds to death from a stab wound inflicted by a German pilot that crashes near an abandoned French residence that the corporals inspect.

I personally interpreted Blake’s death as a symbol of the death of the innocence that the world had its head blindly dug into. The full effects of war and death had really begun to take its toll on the world at this time, as hopelessness and “shell shock” ran rapid from home to home.

The director, Sam Mendes, explained how the events portrayed in the movie were based on stories that his grandfather, Alfred H. Mendes, who served in the war with the British, told him as a child. But otherwise, the mention of a strategic German retreat in order to send the British into complete turmoil and ruin are completely accurate historical accounts of what happened.

Lance Corporal Schofield ends up making it to Colonel Mackenzie, the man in which is supposed to have retrieved the message. The second wave of attack is called off by Mackenzie, who then sends Schofield to the aid post to get his wounds attended to.

The film ends with a breathless and virtually speechless Schofield resting against a tree in the meadows, closing his eyes in one of his first moments of peaceful rest since his journey began.

1917 is a film that beautifully portrays the confusion and blend of emotions that swirled in the hearts of those living at the time, while simultaneously installing a raw feeling of heroicness towards the men that fought the war that should not have happened.